"To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric."

People who think about the Holocaust confront this inevitable dictum of Theodor Adorno. Usually he is quoted to the effect that writing poetry after Auschwitz is impossible, which is not quite what he said. He did say that it was impossible to write poetry "today" (in 1949). It is difficult to know what he could have meant, since good poetry was being written in 1949, including good poetry about the Holocaust. It is also hard to know what he meant by "barbaric," and there is no sign that he gave the term much thought. Adorno made matters more confusing by retracting the remark, not in the form in which he pronounced it ("barbaric") but in the form in which it is quoted ("impossible.")

Generally people are respectful of Adorno, and a lot of effort has been spent trying to make sense of his words. Personally I have never been able to care what Adorno was saying on this matter, if he was saying anything at all. Adorno's explanation of the Holocaust (which I will not go into here, but which I address in my book Black Earth) was simpleminded and wrong. His inarticulate and contradictory mumblings about the Holocaust and poetry have, for seven decades now, distracted us from the actual Holocaust and its actual poetry. Thanks to Adorno, passing judgement (barbaric, not barbaric, impossible, not impossible, etc.) on poetry after Auschwitz has become a substitute for knowing the poetry of the Holocaust.

It is worth knowing. Poets were among the murdered, and some of them kept writing until the very end. The extraordinary Hungarian poet Miklós Radnóti (1909-1944) wrote a poem about mass executions. He wrote his final poems during his own death march. His notebook was discovered in his pocket when his corpse was exhumed. Some of the lines that stay close to me are: "I the root was once the flower/under these dim tons my bower/comes the shearing of the thread/death saw wailing overhead." Radnóti's story has been told, and some of his poems translated, by Zsuzsanna Ozsváth.

Hungarian Jews were the single largest victim group at Auschwitz. When Imre Kertész, a Hungarian Jewish survivor, won the Nobel Prize for literature in 2002, he referred to another writer. Tadeusz Borowski's "stark, unsparing and self-tormenting narratives," said Kertesz, had been a model and an inspiration. Borowski was a Polish poet who witnessed the mass murder of Hungarian, Polish, and other Jews in Auschwitz.

Borowski (1922-1951) debuted as a poet at the age of nineteen in occupied Warsaw in 1942. After his (Jewish) girlfriend was arrested in April 1943, he willingly followed her to Auschwitz, where he helped her to stay alive. Poetry had helped him towards a worldview that Auschwitz did not break but reinforced. His poetic catastrophism, fully formed before his deportation, was unchanged by the gas chambers.

His friends published some of his poems after he was deported. He himself had managed to self-publish a collection called "Wherever the Earth" in 1942. This is the final quatrain of its final poem, entitled "Song":

Night above us. The stars on high

Violet putrefacting sky

Our legacy is scrap iron

and the mocking laugh of generations

His poem "Night over Birkenau" includes the quatrain:

Like a shield cast down in battle

blue Orion amid stars supine

Through the dark an engine rattles

And the eyes of a crematorium shine

I don't know how to catch this in English, but in Polish the title of the second poem echoes the language of the first. The words "over" and "above" is the same word ("nad") in the Polish original. In Polish "night" is "noc." "Us" here is "nami." So we first have "nad nami noc" and then we have "noc nad Birkenau." The three n sounds work together in a way that I also failed to get across in English. But you do see: it is the same night and we are the same people on both sides of the barbed wire.

Borowski's poetry was about the suicide of civilization, but it was not uncivilized. He loved Shakespeare. Few things are older in the history he was taught (in an underground university by an excellent professoriate) than the Greek names of the constellations. His poetry prepared him for the writing for which he is now best known, a handful of short stories about Auschwitz.

Without Borowski the poet there would be no Borowski the writer of prose -- and without his stories we would not have the image of Auschwitz that we do. Although neglected somewhat in recent years, Borowski is perhaps the single most important chronicler of Auschwitz. Perhaps what is barbaric is to try to think about Auschwitz without poetry.

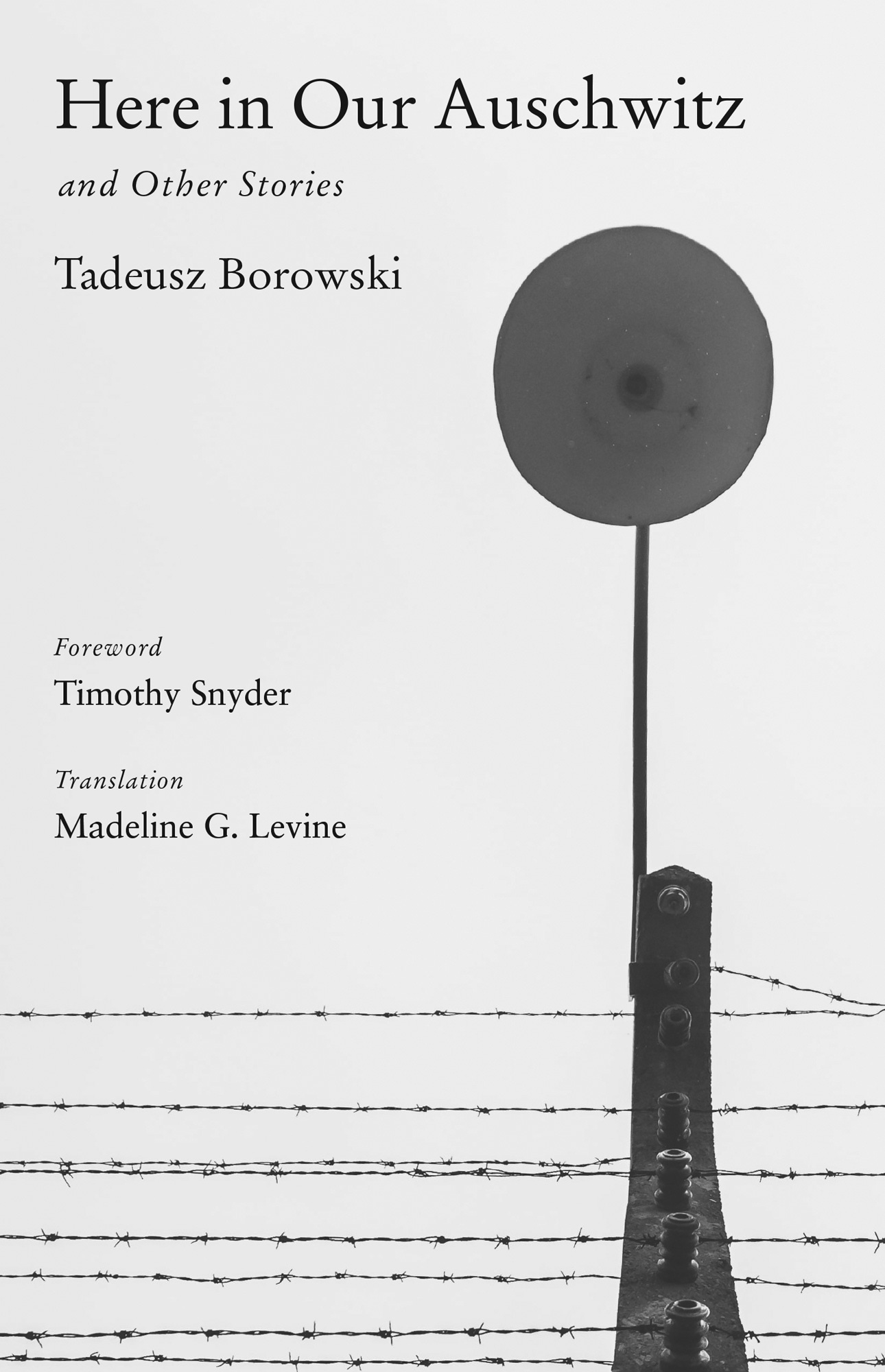

Borowski's prose will soon receive more attention. His fiction has been beautifully translated from Polish into English by Madeline G. Levine. It was humbling for me to write a foreword to these stories, a task that led me back to the poetry (and to translate these few lines). The stories published under the title Here in Our Auschwitz are merciless and yet not unkind; they refuse to allow us to separate the inhuman from the human; it is their very plausibility that haunts. I will have more to say about Borowski, Auschwitz and us soon.

One can write poems. One does. Adorno is himself poetizing in this phrase. But I take it that "after Auschwitz," of the titanic poetry of Christian civilization in Europe there's little left except its doppelganger, barbarism. Celan is possible. Dante is not. (Or am I simply being perverse?)

So I finally succumbed and read this piece, deciding not to wait for the audio. These are superb reflections and I'm certainly sympathetic to your overall sense of Adorno's remark. But I also think that perhaps Adorno, irrespective of how one interprets his gnomic thought here, touches upon something important. We can disagree with Adorno or find him frustratingly cryptic in this matter and yet use him as a signpost in a certain way.

Zizek says somewhere that it is not poetry but prose that is 'impossible' after Auschwitz. In my view he makes the mistake of equating prose with descriptive realism of the documentary sort (but what authentic documentary really does this? As an example, and perhaps a wholly appropriate one here, I'd give a shout-out to The Ister, the extraordinary 2004 film that deals with the thought of Heidegger) and then finds such a form 'impossible' after the Holocaust. In your current profession this idea might be even less appealing to you than Adorno's (!) but in all seriousness it's hard to think of truly important prose in any register that isn't also 'creative' and for the same reason, and if one can risk this word, 'poetic'. In other words 'bad' prose might well just be descriptive. Differently still there might be for instance excellent historical works that are great descriptions of the past but that are nevertheless not more than the sum of their research. This could be considered a kind of 'bad prose' that is in turn open to Zizek's criticism. But from Heorodotus to Timothy Snyder 'good' historical writing has also involved modes of memoir or autobiography, poetic economies of memory, the fabulist or the fantastical, not to mention the densely theoretical. And of course there are genres of non-fiction (surely a misnomer!) prose, including some I've just highlighted, that are even less susceptible to the documentary charge. In fairness Zizek is as always relying on specific psychoanalytic genealogies. I don't want to get too sidetracked here but the Lacanian 'truth-has-the-structure-of-a-fiction' dictum is operative in the background most days with him [Zizek]. In this context the documentary inasmuch as it refuses the fictional mode also misses the encounter with the truth of a situation. The poetic mode meanwhile and to the degree that it represents a 'dream' of language (elsewhere Zizek calls poetry that which is created after ordinary language is tortured, polemically opposing the idea of the poetic word as absolute creation, as in Heidegger and others) is more adequate to representing truth and therefore Auschwitz. Or for that matter a poetic novel (Zizek uses Jorge Semprun as an example) can do the same.

But Adorno might still have a point. Perhaps it ultimately comes down to a certain opposition. Is poetry to be understood as 'aesthetics' or as 'truth'? One would think that a poem worth the name would never have to choose between the two but there might be something more foundational to such a division. On the side of aesthetics there are histories of humanism that get implicated. We are all post-Kantian on this score. We might wish to argue (as Harold Bloom often did very churlishly) that the 'aesthetic' is a category as old as Longinus. The problem here is that even though humans everywhere and at all times (including apparently our cave-dwelling ancestors, including even our Neanderthal forebears) have engaged in artistic activity and have consequently had a sense of what is 'beautiful'.. the understanding of the human or the world etc have been dramatically different in these various contexts. To use a very crude example can a sunset be considered 'beautiful' or aesthetically significant without there being no frame of meaning within which it is placed? Or better still are those aesthetics altered if one considers the son a god as opposed to a completely scientifically explicable ball of fire? As Heidegger would have it an authentic poem (not every poem... in his schema Goethe is great for aesthetic reasons but Holderlin is so for reasons of 'truth' and hence ultimately a more foundational figure) opens a new regime of truth or meaning and by extrapolation one might say re-orders the world. To repeat the example Goethe is the best practitioner of language with the world or regime of truth that he inherits whereas Holderlin fashions a new one.

Adorno spent a fair bit of his time railing against Heidegger but his dictum in this case might presuppose a similar schema. Perhaps poetry in the aesthetic sense cannot represent the 'truth' of the Holocaust. There has of course been great Holocaust poetry. You know all the examples far better than I do. But does such poetry for all its brilliance, all its uncanniness really approach a newer truth? Celan (I'm most comfortable referring to him in this context) tortures language in the Zizekian sense but does he inaugurate a new understanding of the 'human' and human history and politics? Or differently does the Holocaust itself force us to rethink all our previous ways of defining the human so that there might be poetry possible after Auschwitz but only to the degree that it accounted for this seismic shift? Perhaps there were these concerns drifting through Adorno's mind when he said what he did...

Needless to say I am not necessarily endorsing any of these thinkers or any of these positions. Actually I even think that the sacrilegious 'use' of the Holocaust is itself problematic for many of the reasons you've discussed in your work and public interventions. If the Holocaust begins a new time, if it has to be divorced from all history, if it is unique in every sense imaginable, it loses the ability to become instructive at a more profound level. On the other hand if it is the 'worst' (not the only 'worst' but one of the very 'worst'... ) without detaching itself from all previous archives of human history and experience.. well, then it will always have something very deep to teach us. Having said all this I must confess to oscillating between both possibilities. I completely absorb and accept everything that you write (or say) in this regard. But I also wonder whether many of the philosophers who've examined the Holocaust, especially in post-war France, might not be right when, and irrespective of their internal debates, they try to understand this awful history as not simply or even in the first instance the 'worst' as a matter of degree but, and much more so, the 'worst' in a truly qualitative register. In such a line of thought one cannot strictly compare the Holocaust with for instance the American institution of slavery. Both would be differently 'unique'. The historical genealogies common to such events or including all those very sordid episodes of colonial history (specially all the camps that were direct precursors to the Holocaust... or all the camps that have followed in the wake of the same.. right down to our day..) are crucial and need to be endlessly re-visited but at each node of that history something very singular nonetheless comes about which if you will transcends all our analytic categories and which then requires a more rigorous philosophical account.

In such 'impossible' circumstances do humans really 'experience' things? They somehow survive them (if they're at all lucky enough to do so) but is this an 'experience'? Don't we need a new vocabulary so that spending two years or more on border camps 'in cages' with very basic necessities like fresh clothes and soap and baths and medical attention being denied to children is not also classified as 'experience' the way attending a performance at Lincoln Center is 'experience'? And if one agrees to this what language and metaphorics and ultimately tools might a poem employ to adequately register such 'impossible' experiences? Perhaps a great Holocaust poem can tell us what a human might feel or experience in these circumstances. Perhaps. But can it do so while simultaneously placing the human 'under erasure' (Derrida's term but elsewhere Catherine Malabou in her New Wounded, coming at it from a neurological perspective as well, makes the claim that humans who've experienced don't just exhibit severe trauma but in many cases cease to be their former selves at all and to the point where no vestige of the human formerly bearing that name is retrievable.. in other words psychic injury that is the exact equivalent of physical brain injury in terms of its total destructiveness)? Not because one will have accepted the violence of the oppressor but that one will have conceded only this... if such a thing is possible, has been possible, will continue to be possible... then we need newer ideas, newer words to recalibrate everything. Only then will the Holocaust have been singular and exemplary at one and the same time. So too with poetry (or prose) hoping to be equal to the same.

Celan perhaps does all this. Heidegger through all his silence probably thought of him as a poet of truth. But once again I am not trying to take a position here. I am only trying to think what Adorno might only have gestured at. We don't have to agree with him but, and despite the obscurantism, perhaps we should care a bit more about his remark...