President Vladimir Putin delivered his annual state-of-the-nation address last week in Moscow. Most of it was boring, and the remainder was selfish. Lengthy platitudes and indignant expostulations are the natural modes of expression for the leader of an aging regime. But the address deserves more analysis to than it has received. Attention to what the Russian president said, and what he did not say, can give us a sense of what is wrong with the Putin regime, and what might come next. This is the first of three brief essays.

1. Pandemic. It is bad news for his regime that President Putin spent more time on this issue than on any other. Putin is a skillful teller or tales, one of the best in the business, but his lies work best when they are quick, audacious, and totally unconnected to reality. The disease, and Russia's poor handling of it, pinned Putin down to a much more conventional and meandering mendacity.

His boast that "many leading countries" "were unable to deal with the challenges of the pandemic as effectively as we did in Russia" is not very persuasive. Russia systematically issued false information about the number of covid deaths, which are in fact among the highest in the world. Putin inadvertently referred to this when he spoke of "sad and disappointing numbers," in a reference to higher-than-expected mortality last year. It is precisely the unusually high number of excess deaths that indicates that Russia's official figures about covid deaths cannot be correct.

Last year, Russia chose to spread propaganda to the effect that covid was an American biological weapon, and sought generally to weaken public health in western democracies. This year, the Russian government has undertaken a foreign policy of vaccine diplomacy without having vaccinated its own population. The vaccine diplomacy is not going especially well; Slovakia charged this month that it did not get what it paid for.

None of the vaccine foreign policy was mentioned in the address, which is also a bad sign for Putin. He does not really have domestic policy, nor he capacity to generate it; the way the regime works is to generate foreign policy to distract or excite a domestic audience. Russia might not be good, but it is great: that is general idea. His line to domestic audiences for quite some time was that Russia was able to help the world survive covid; now he has been pushed back to the much more conventional claim that everything at home was harder than expected.

2. Opposition

As Putin was giving his speech, the health of one particular Russian was a concern of people around the world. The most striking thing the Russian government did in health policy last year was to poison its leading opponent, Alexei Navalny. The physician who treated Navalny died suddenly. Navalny himself recovered in Germany, and then chose to return to Russia. He was arrested at the airport and quickly sentenced to two-and-a-half years in prison on a demonstratively bogus charge: that he failed to meet conditions of a previous sentence while he was lying unconscious, poisoned by the state that sentenced him. As Putin was speaking, Navalny was undertaking a hunger strike in prison to protest a lack of access to medical care. Putin never mentions Navalny, which smacks of something like fear.

The reason that Navalny has a following in Russia is that Russia has a problem with oligarchy, and Navalny is a public figure who is willing to talk to about it. As Navalny returned from Germany to Russia, he released an exposé about a disgustingly opulent palace, which he claimed was owned by Putin. After a series of confusing denials, the Putin regime settled on its laughable official position: the palace existed, and was owned by an oligarch, not by Putin, instead by a childhood friend of his, his former judo partner.

3. Oligarchy

The theme of President Putin's remarks about the pandemic was the hard work of people from all walks of life. None of these people was apparently important enough to mention by name.

What his theme of "people's solidarity" elides is that wealth in Russia is grotesquely maldistributed, and that his regime makes this state of affairs legal and inevitable. The Putin regime is the victory of one clan of oligarchs over other clans, and the merger of the victorious clan with the state. His claim that "we are making all major decisions concerning the economy through a dialogue with the business community" thus has a comical resonance. Much of the policy work that Russia does is farmed out to friendly oligarchs. But to be a normal member of the "business community" in Russia is quite difficult, since no one except friendly oligarchs know how the law will work in advance.

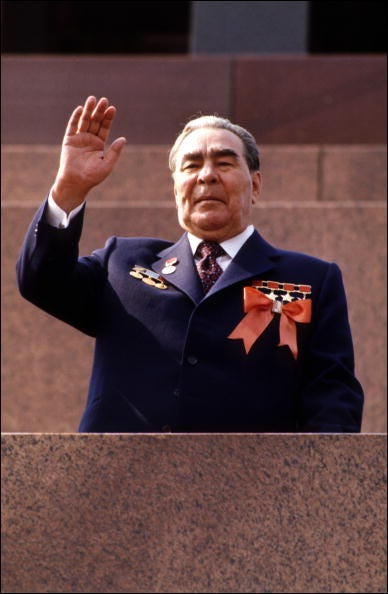

Much of Putin's address amounted to encouragement to Russians to do their jobs better. In this in many other ways (chiefly its alternation between the boring and the weird) it was redolent of the Brezhnev era. Nothing very different is being promised; figures are mentioned and targets are set; everyone should just work harder and be less corrupt, and be satisfied with the rhetorical crumbs that fall from the leader's table. The basic problem in Russia is the weakness of the rule of the law, and that that cannot be solved in oligarchical conditions. Oligarchy is the area that Putin cannot touch, because it is the essence of his rule.

“The basic problem in Russia is the weakness of the rule of the law, and that that cannot be solved in oligarchical conditions. Oligarchy is the area that Putin cannot touch, because it is the essence of his rule.” I was thinking about these sentences and how they relate to some degree in the countries under authoritarian rule. Weakness of the rule of law cannot be solved in an oligarchy and Putin won’t touch the oligarchy because Putin’s rule rests on it. So in maintaining that which weakens snd eventually destroys the rule of law, I would think what would happen would eventually be a descent to lawlessness in a Country, given some unlucky circumstances. COVID-19 is one bit of unlucky circumstance for Putin. A Country with enough unlucky circumstances and a leader only interested in maintaining his own status without regard for the people eventually ceases to exist. What happened in the Congo is one example. What is going on in Venezuela is another example of a descent into lawlessness. Large swaths of the Country are no longer under Maduro’s control, but are under control of gangs, mostly from Columbia. The more Maduro tries to hold power, the more the Country falls apart. I think Putin is smarter than Maduro, but he is boxed in by the Oligarchy which sustains his power. He rules only as long as he lives and/or doesn’t have a big screw-up or a series of bad luck events. I guess Putin wants to live comfortably but at what price?

I hope we here in the US can learn from these various examples. I’m not so sure we will learn though given we have entrenched oligarchs calling the shots here.

Aging regime is so apt when we recall that P's longevity is in second place only to Stalin, whose primacy kept him above the stress & health issues to which his rivals (everyone!) succumbed and enabled his homicidal bent beyond the FBI profile retirement age for serial killers here. Power addicts are the worst prospects for the inevitable helplessness if one lives that long. How long do you give this ruler & his enablers?