My train to Zaporizhzhia came in four minutes early. I had to smile. The Ukrainian trains, despite everything, are very punctual. My overnight from Chełm in Poland to Kyiv had been right on time. And then the overnight train from Kyiv to Zaporizhzhia was ahead of schedule. I was here for the opening of a school, but had much else on my mind.

Zaporizhzhia is deep in the southeast, about twenty miles from the front. The name means "beyond the rapids"; the industrial city sits astride the Dnipro River, at a site critical for commerce and conquest since ancient times. For me, the ride to Zaporizhzhia was towards the end of a longer European journey, which took in nine other countries aside from Ukraine.

By the time I got to Khortytsia, the large island in the middle of the Dnipro that looks down the river towards the city, I was thinking of all the connections between the land where I was standing and the countries I had just visited, links that are integral to history but often lost to memory.

For Ukrainians, Khortytsia was the site of the capital of a Cossack state. But, as I was reminded while walking around the island, they know that its human history is thousands of years older.

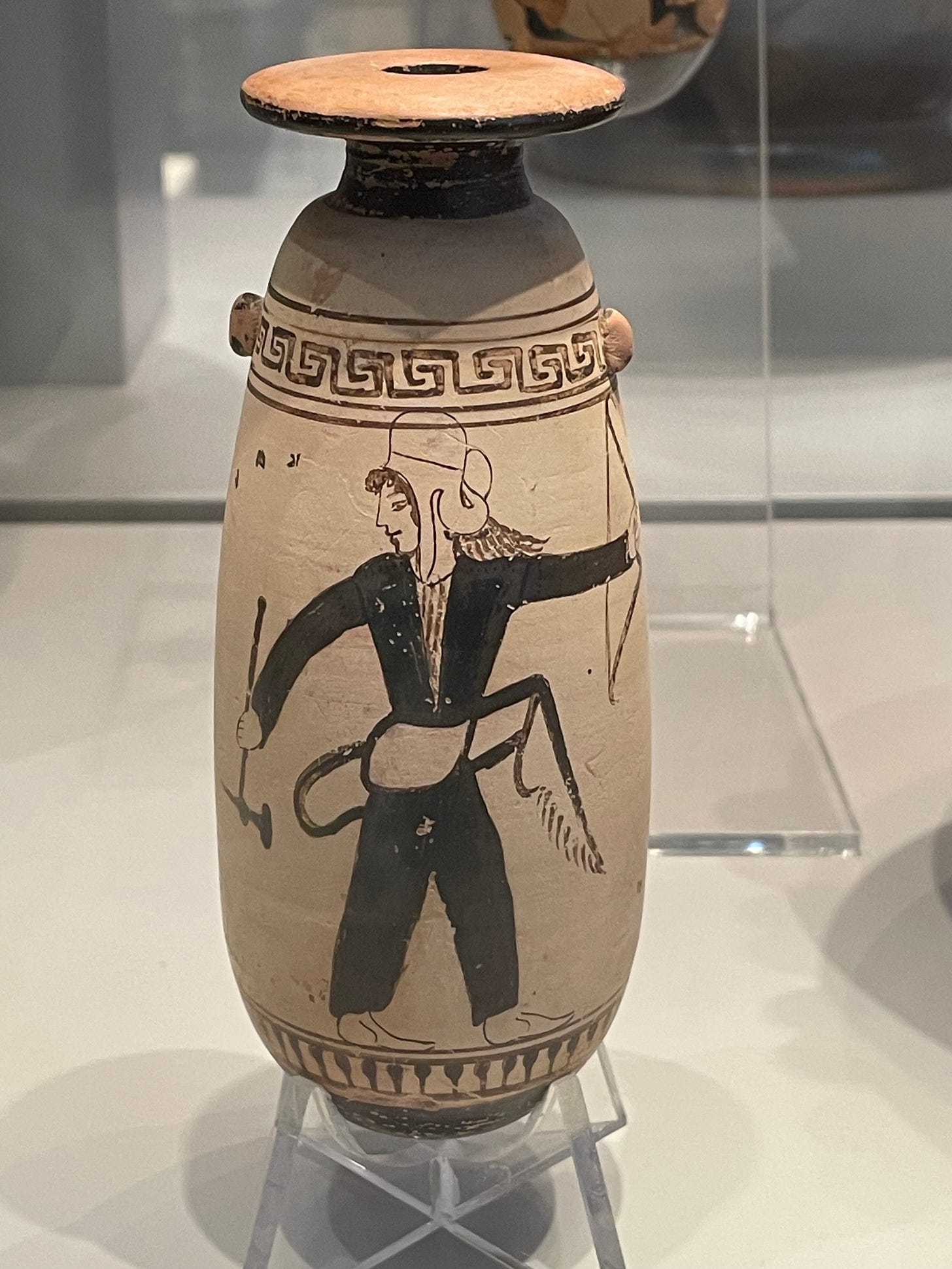

The Dnipro River itself has a Scythian name. The Scythians were a great power of antiquity, respected by Herodotus for having defeated the Persians. The military power of the Scythians, at its height, would have been greater than all of the contemporary Greek city-states put together. And Greeks and Scythians did fight; this is the source of our cultural memory of Amazons, who were, in reality, Scythian female warriors. I got to Khortytsia a few days after a visit to the Altes Museum in Berlin, on which such a warrior can be seen on a Greek vase.

In Greek myth the great heroes encounter Amazons. In the Scythian side, the story seems to have been that Hercules had an encounter with their snake goddess (on Khortytsia) that founded the Scythian people.

That generative story suggests the mainstream of Scythian-Greek history. What we recall as classical Greek civilization existed in an economic and cultural synthesis with the Scythians, people who inhabited the lands north of the Black Sea, what is now Ukraine. Insofar as we see ancient Greece as part of our tradition, we should also see the Scythians, Khortytsia, Zaporizhzhia, Ukraine.

The Scythians were succeeded in the lands of Ukraine by the Goths, a Germanic people we associate with the fall of Rome. After centuries of apparent dominance and prosperity, they were driven west from what is now Ukraine by the Huns in AD 376. Soon thereafter however the Goths defeated a Roman force, killed a Roman emperor, and sacked Rome (although, St. Augustine tells us, they spared the churches).

Thereafter Goths founded and ruled states in what is now Italy, France, and most notably Spain. The state that the Spanish regard as foundational, that is, the state that Ferdinand and Isabella "reconquered" in 1492, was a Gothic kingdom, ruled by people whose descendants came from Ukraine.

On my journey I made a point of finding the Gothic crowns on display in Madrid and Paris. None of the museum descriptions were clear on whence the Goths had come. But as with the rise of Greece, so with the fall of Rome: the history of Europe and the world is incomprehensible without peoples from what is now Ukraine.

Looking downriver at the rapids from Khortytsia island, I see a place where Vikings struggled. The main thrust of the Scandinavian exploration than began c. 700 AD was actually not the west but the east. For almost half a milennium Vikings raided and traded across a huge swatch of eastern Europe and western Asia. Perhaps their greatest achievement was the establishment of a state in Kyiv. Its most ambitious ruler was the also the greatest Viking warlord, Sveinald or Sviatoslav. He made war across a huge range of territory, from the Balkans to the Volga. He seems to have been killed, returning from the Balkans, trying to cross the cataracts that can be seen from Khortytsia.

Sviatoslav was the father of Valdamar, remembered by Ukrainians as Volodymyr. The history of Kyiv is thus an integral part of the history of Scandinavia as well as that of Ukraine.

Once again, though, the history is stronger than the memory. How many Danes know that their great medieval king, Valdamar I, was a direct descendant of Valdemar/Volodymyr of Kyiv? And it is not only history but story. The Norse myths, like the Greek ones, have much to do with these lands. In lectures in Stockholm and then Oslo, I tried to remind people of this.

History should not justify war, regardless of how accurate or inaccurate. Still, when one is standing on Khortytsia, it is hard not to marvel at the oddity of Russia's present claims. Putin's story about why Russia must invade Ukraine is based upon his misunderstanding of a Viking colonial trope that does not concern Kyiv and could not have concerned Moscow, which did not exist at the time.

In the occupied zones of Ukraine today, Russian policy is to suppress Ukrainian culture, and to claim as Russian artifacts that were found in Ukraine. In one of the saddest episodes, Russians looted all of the Scythian artifacts from a museum in Kherson. In September 2022, Russia even went so far as to claim the entire region of Zaporizhzhia as part of the Russian Federation. Such a claim is illegal, and in any event extends to lands that Russia does not even physically occupy.

It is meant, at least in part, to shield Europeans and others from the historical connections between their countries and the lands of Ukraine. Europeans are supposed to ask: is it Russia or not? And to forget the Scythians and Greece, and the Goths and Rome, and the Vikings and Kyiv.

In Zaporizhzhia, on the mainland, I met my favorite Europeans at a history lesson. I had been invited to join in the opening ceremonies of a new, underground school in the city. The school is underground not in some metaphorical sense, but physically. Russian missiles take about forty seconds to reach Zaporizhzhia, which is not enough time to get to shelter. And the Russians target schools.

Some of the children of Zaporizhzhia have departed for other places in Ukraine. At the same time, many children now in Zaporizhzhia have fled from nearby cities under Russian occupation, such as Melitopol. So that they can be schooled, basements of schools have to be used full-time, and new entirely-underground schools are constructed. The underground school that I visited was cheerful, well-lit, and generally a delight.

It was in that school that I met my favorite Europeans.

For the previous three weeks, I had been meeting Europeans in universities, government departments, and cafés. And I was glad to do so and enjoyed the discussions. I kept having to answer some of the same questions, though. What will Trump do? And what will Putin do? What about the fascists? And the chaos they bring?

And, of course, I did my best to answer, although in some sense the line if questioning was itself the problem. Russia has gone the way it has gone, and America is going the way that it is going. Europeans have to act. To sit and wait for Putin or for Trump is to choose a passivity that itself has consequences. Europe's connections to Ukraine should be obvious enough, and not just from the past. Ukraine is Europe's chance to act, a chance that has to be taken.

I have a video of favorite Europeans that I wish I could show you. The kids were beautiful in their Ukrainian embroidered shirts (vyshyvanky); one freshly crewcutted boy was wearing a suit. Their parents had treated this day as a special occasion.

This was the first time in their lives, I realized, that these boys and girls had been in an actual classroom. The Russian invasion began right as covid was ending. Two years of covid seclusion had been followed directly by three years of war. The kids were buoyant. For me, it was the first time during a long trip when I could pose the questions.

And so I asked them: "Is coming here better than remote school at home?" And they all started talking at once. “Yes! Yes! Yes!” The teachers got them to raise their hands. Then the answers came in beautiful, fully-rounded Ukrainian sentences. I am watching the video again right now... "You can meet with your friends... If you don't understand something you can raise your hand and ask... The teacher can make sure you understand… You can be together..."

The underground school was built in half a year. That would be impressive under any circumstances, let alone those of an active war. Leaving Zaporizhzhia, heading back on the main boulevard in the direction of the the train station, I appreciated again the brickwork of the buildings. In many buildings there are two colors, because some bricks are older and some are newer.

My favorite Europeans take matters in to their own hands. This is what Europeans in general will have to do.

Tomorrow will mark the end of the third year of Russia’s war against Ukraine and its people. If you wish to help Ukrainians, consider supporting Come Back Alive (Ukrainian NGO that supports soldiers), United 24 (the Ukrainian state platform for donations, with many excellent projects), RAZOM (an American NGO, tax-deductible for US citizens, which cooperates with Ukrainian NGOS to support civilians), or Documenting Ukraine (a project I help run that helps to give Ukrainians a voice, also tax-deductible for Americans).

And we in the United States will also have to take matters into our own hands. My question is, "Will we?"

We should, as Trump was not even elected by a majority of Americans and probably about half of his voters are not hard-core MAGAts. Authoritarians are usually given their power. We, the people, must give Trump nothing.

Tim, every time I am sitting and seething (bad for one's blood pressure, I know) about the current situation, one of your posts pops up in my inbox and, after reading it, I find myself calmer and more educated than I was before it arrived. Thank you!!!