As we contemplate a Russian invasion of Ukraine, let us begin from the people who are most concerned, the Ukrainians, and with what they have to lose. About twenty-five miles from the Russian border lies Kharkiv, Ukraine's second-largest city. The last time Russia invaded Ukraine, in 2014, it staged a rebellion in the city, which failed. Its supporters charged the opera house, mistaking it for town hall. This time, Kharkiv would very likely be stormed in the first week of the war by the regular Russian army.

Last fall, Kharkiv premiered “King of Ukraine,” an opera based upon the true story of a modern aspirant to a Ukrainian throne. The libretto was written by Serhiy Zhadan, a poet and novelist who was hospitalized with head wounds after the attack on Kharkiv in 2014. He was severely beaten after refusing to kneel and kiss the Russian flag.

In a series of six posts (this is the fifth), which draw from my book The Red Prince, I will tell the true story of the man who once wished to be king of Ukraine. Its lesson: a nation is what you love, not what you inherit.

In interwar Europe, democracy collapsed in nation after nation, destroyed by revolutions from the left or coups from the right. Multiple attempts to establish states in Ukraine failed. The Red Army eventually took control. Ukraine became a Soviet republic.

When the situation seemed hopeless, Wilhelm chose Paris, where he established himself in 1925. He spent something of a dark decade in the city of lights, living four lives: one as a member of chivalric orders protecting the traditions of aristocracy, one as a member of secret societies seeking to create an independent Ukraine, one as an agent of intelligence services -- and one as a devoted client of night clubs. It was a life in which he was either undercover or on magazine covers, of alternating secrecy and celebrity.

Modernity was emerging the form of the state and ofmass culture: both insatiably desirous of knowledge, be it coded reports on central European politics or gossipy tabloid accounts of charity gold tournaments. Wilhelm's was a dramatic example of the life of the political émigré in France -- but characteristic in its insistence that there was something inherently important about pleasure, about the choice of beach towns, or golf clubs, or husbands for Montmartre dancers. It was an existence separated from power but desirous of it, in its very languor and luxury also a life of suspended choice.

Although his father had disowned him and the Austrian republic had nationalized Habsburg property, Wilhelm had a kindly uncle who made sure that he received an allowance. In Paris he made the best of things, renewing his acquaintance with the British royal family, and making friends with French industrialists.

He remained optimistic that his cousin Otto von Habsburg could lead a Habsburg restoration that would bring the family back to power, and that an independent Ukraine could somehow be recreated when the Soviet experiment failed. He attended closely to events in Ukraine, and his command of the Ukrainian language actually improved in his Paris exile. In 1933, when Soviet policy led to a terrible famine in Soviet Ukraine that killed millions of people, he tried to raise money and awareness.

Soon after that his lifestyle brought him a new sort of trouble. He was befriended by Paulette Couyba, a clever adventuress possessed of a deep wardrobe and connections to French communists. She exploited what she suggested was her love affair with Wilhelm to defraud wealthy French citizens. She promised a quick profit on their investments, explaining hazily that investments would yield huge returns once the Habsburgs were restored to their Austrian and Hungarian thrones. In 1934 Couyba was arrested. She mounted a clever and mendacious defense in court: that she was a simple Frenchwoman seduced by a charming foreign prince, who tricked her into to carrying out schemes that she did not understand. Wilhelm had no need for money and had never been present when Couyba defrauded her victims; but he was added to the complaint as a defendant, and the trial went poorly for him. The French tabloid press seized the angle of a degraded Austrian archduke exploiting an innocent French. This was inaccurate but made wonderful copy. He fled the country.

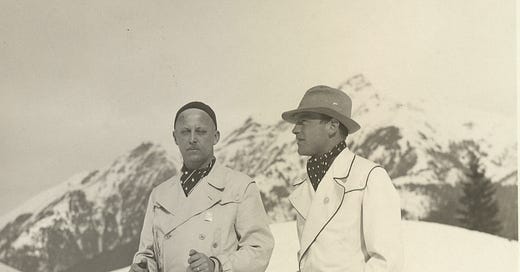

Wilhelm then found himself in an Austria that was leaving behind an imperial past. He made the best of the late 1930s in Vienna, the capital of European decadence, living with a series of beautiful women under a series of assumed names, climbing mountains and skiing back down them with handsome ski instructors. He never gave up his dreams of a Ukrainian kingdom, plotting with his aristocratic friends to install a monarchy in Kyiv after Soviet power was driven out.

In the late 1930s, Wilhelm was a pretender to the throne of a country that did not exist, Ukraine, and a citizen of one was ceasing to exist, Austria. In 1938 Austria was annexed by Germany in the notorious Anschluss; without leaving Vienna Wilhelm found himself a subject of the Third Reich. During the Second World War he spied for the French and the Americans, only to be arrested at its end by the Soviets. He was taken by night from the imperial capital of his ancestors to the capital of a Ukraine the Soviets had made their own.

Thus Wilhelm reached Kyiv, the city of his dreams, wearing a blindfold instead of a crown, borne to a dungeon rather than a throne. It was the last journey of his life.

(To be continued)

Some beautiful writing that accentuates the power of a remarkable story.

A family of aristocrats with money and no apparent useful skills schmoozes it way around European elite society for multiple generations without being reduced to lifestyles more consistent with their contributions to the general welfare. It is remarkable that the fabric of civilization made it possible for such a pack of leeches to survive in grand style for so long and still today makes it possible, albeit with different schmoozers, mostly from new lineages.