King of Ukraine (2): Habsburg Ambition

A bit of Ukrainian history as we contemplate a Russian war

As we contemplate a Russian invasion of Ukraine, let us begin from the people who are most concerned, the Ukrainians, and with what they have to lose. About twenty-five miles from the Russian border lies Kharkiv, Ukraine's second-largest city. The last time Russia invaded Ukraine, in 2014, it staged a rebellion in the city, which failed. Its supporters charged the opera house, mistaking it for town hall. This time, Kharkiv would very likely be stormed in the first week of the war by the regular Russian army.

Last fall, Kharkiv premiered “King of Ukraine,” an opera based upon the true story of a modern aspirant to a Ukrainian throne. The libretto was written by Serhyi Zhadan, a poet and novelist who was hospitalized with head wounds after the attack on Kharkiv in 2014. He was severely beaten after he refused to kneel and kiss the Russian flag.

In a series of six posts (this is the second), which draw from my book The Red Prince, I will tell the true story the man who once wished to be king of Ukraine. Its lesson: a nation is what you love, not what you inherit.

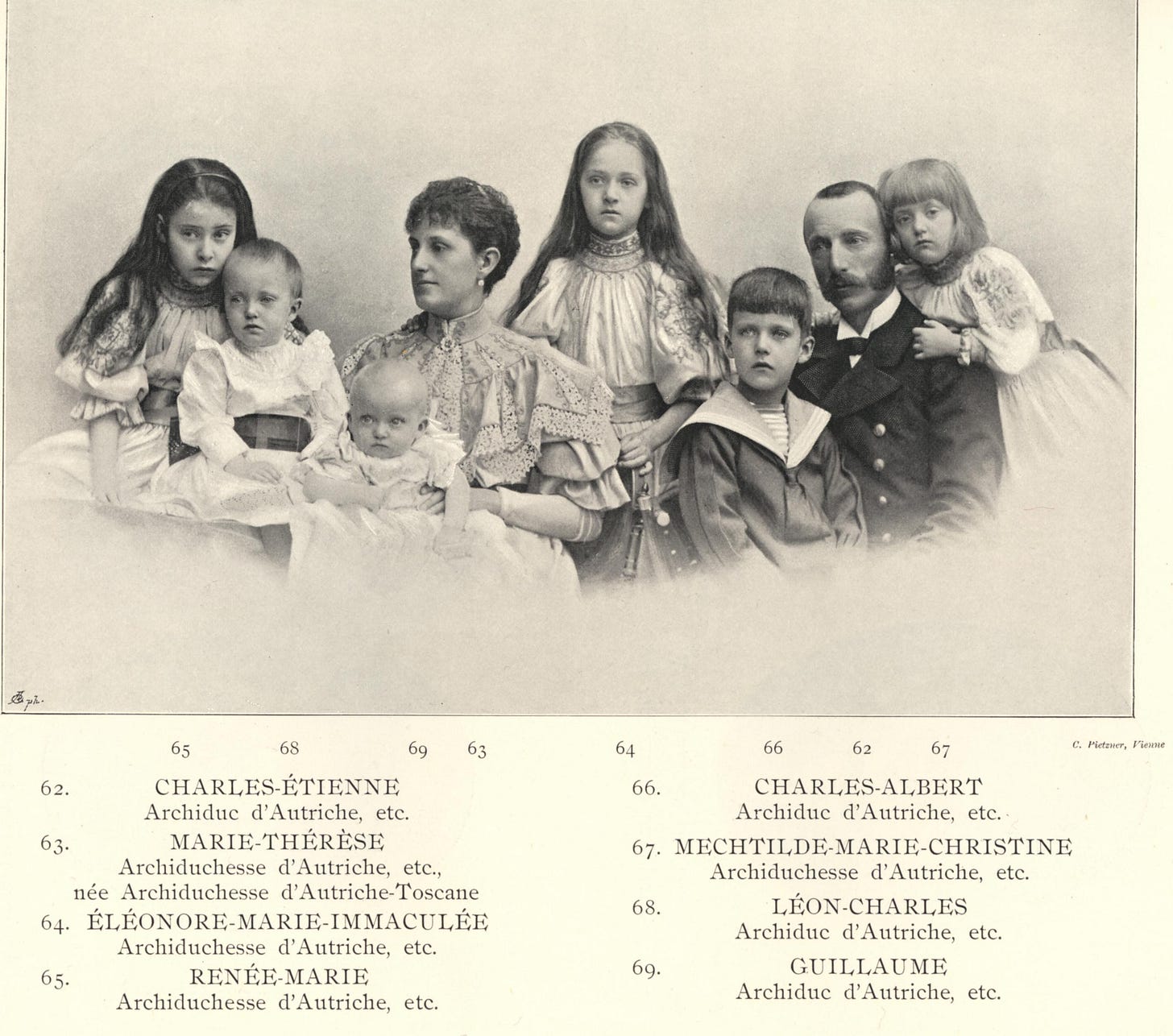

Wilhelm Franz Joseph Karl von Habsburg-Lothringen was born in 1895 in the Austrian port of Pola on the Adriatic Sea, the youngest son of an Austrian admiral, and an archduke of the imperial blood. Wilhelm's father, Archduke Karl Stefan, raised his six children by the sea, and on his various yachts. Much of the first eleven years of Wilhelm's life was spent sailing around the Mediterranean, as the family visited ports of call in Europe and the Near East. Though the family traveled "incognito," they were met by diplomats and royals everywhere.

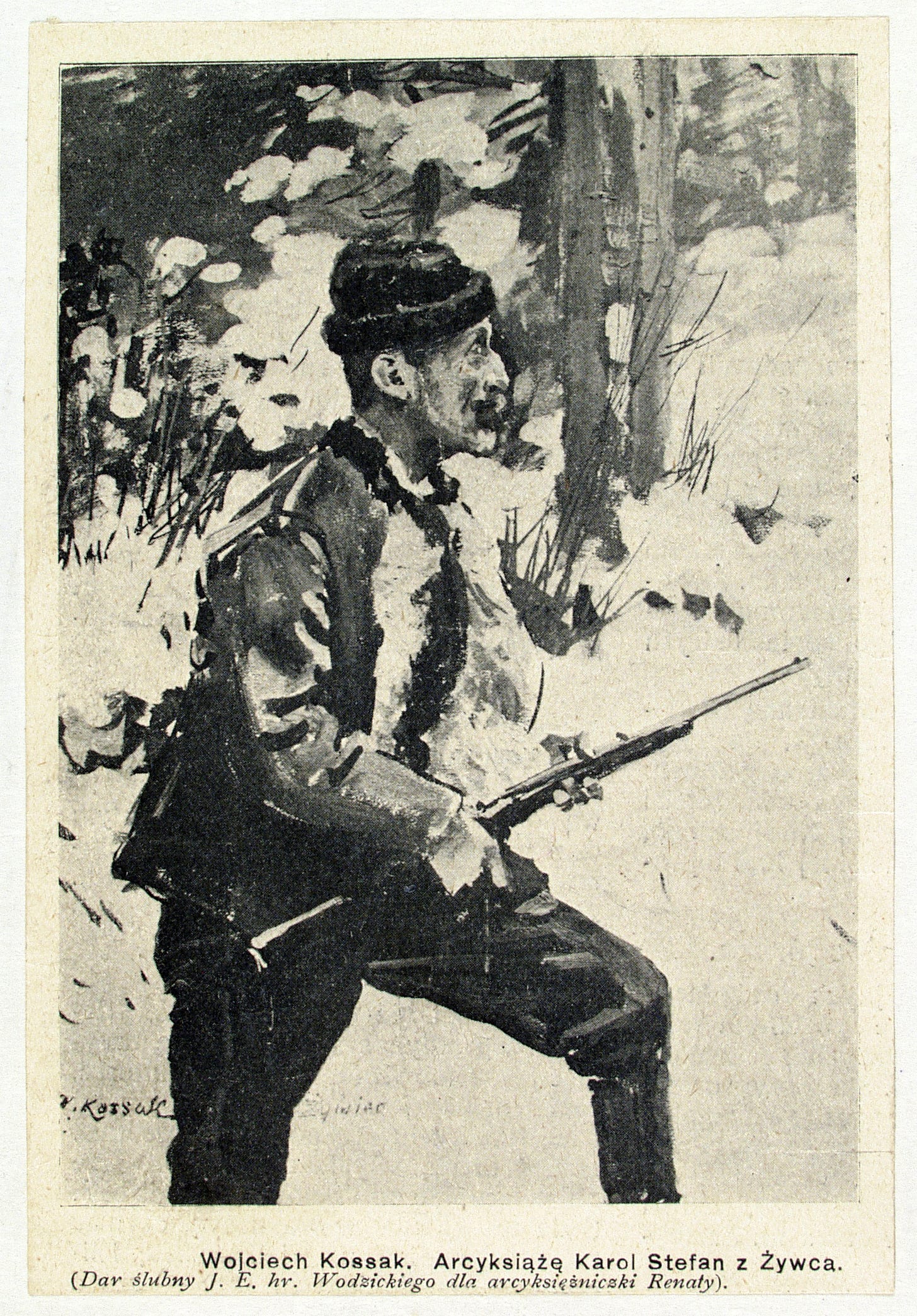

Wilhelm's mother Maria Theresia was a Tuscan princess, so Wilhelm's mother tongue was Italian. She was also a Habsburg archduchess in her own right, and her husband's second cousin: man and wife were descended from the same emperor. Karl Stefan spoke German, the language of empire, to their children. Upon retirement from the navy, however, he made a fateful decision about his own fatherland: he became Polish. To choose Poland in Pola might seem whimsical, but his decision flowed more from calculation than imagination. Karl Stefan's choice to become Polish lay in the best traditions of his imperial Habsburg forefathers.

The Habsburg family had ruled much of Europe for half a millennium. Habsburg emperors had spoken Spanish, Italian, Czech, and German, as the centers of power shifted and as the moment demanded. Habsburg archdukes, male blood relatives of the emperor, were groomed for kingdoms. Archduke Karl Stefan decided, in his maturity, to adapt this heritage by preparing himself for a claim to a Polish throne.

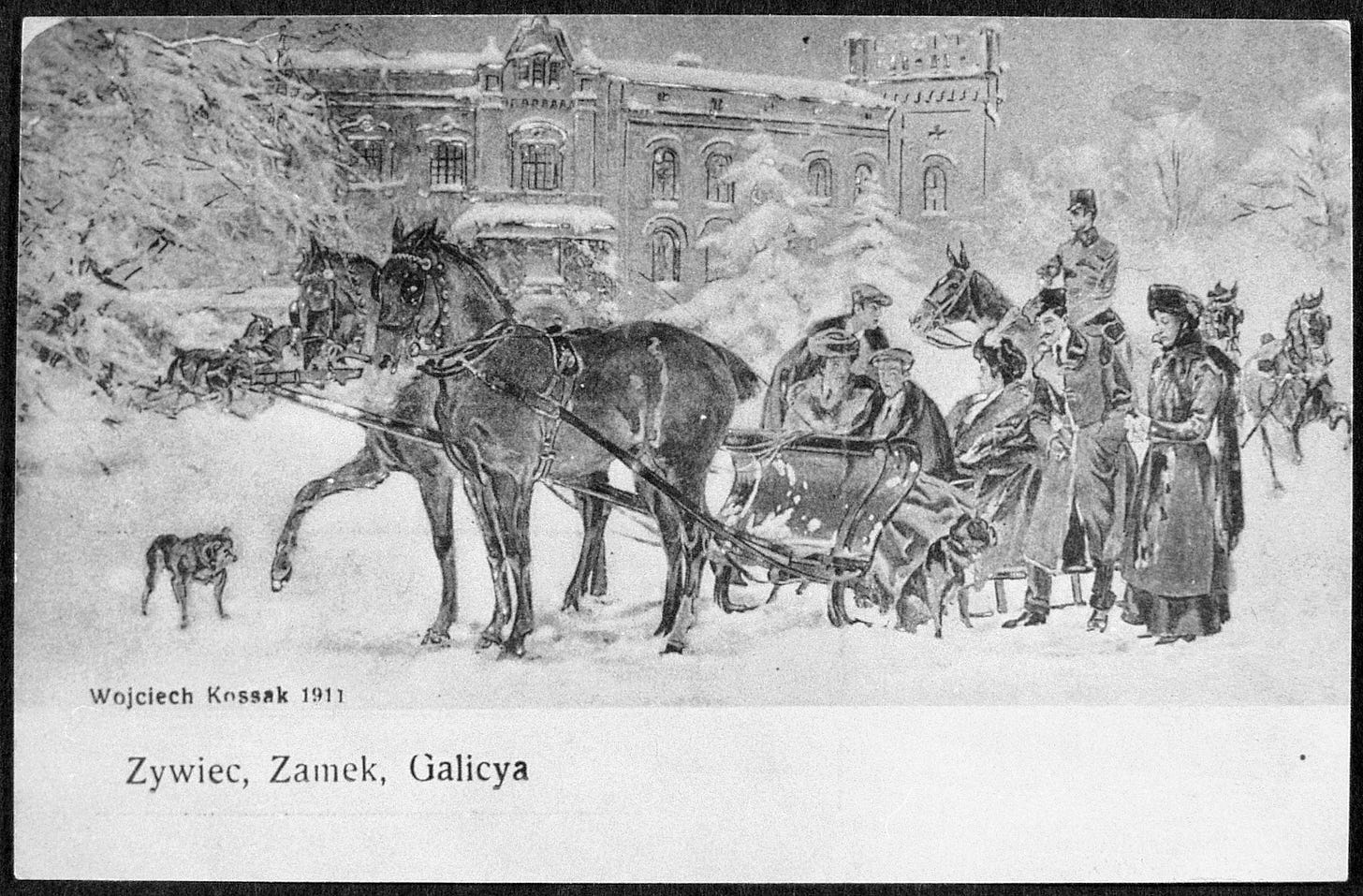

Poland was an imagined kingdom, for the time being, its lands having been partitioned among empires more than a century before. Like all good dynasts, Karl Stefan had an eye on the future, a future which would belong to patriots rather than aristocrats. It was a time of national questions, but some questions have answers. National unification seemed to be the order of the day. Italy had unified after defeating Austria at the Battle of Solferino in 1859. Germany had unified after defeating Austria in the Seven-Days' War of 1866. Could Poland be far behind? Poles might recreate Poland themselves, and then wish -- following the recent examples of Bulgaria, Romania, and Greece -- to elect a foreign king. In 1907 Karl Stefan moved his family from the empire's sunny south to its far north, to the landlocked and much colder Austrian province of Galicia.

Galicia was the Habsburg crow land added in the late eighteenth century, in the empire’s northeast. It was created from lands taken from partitioned Poland, and was home to Poles, Ukrainians, and Jews. By 1907 it was a major center of Polish culture, as the Polish gentry had achieved a high measure of autonomy. But it was also the center of a Ukrainian national movement, directed in the first instance against that Polish dominance. In Pola, in the imperial south, it had been possible to think of a Polish destiny without thinking of Ukraine. In Galicia, the two national questions were intertwined.

The move to Galicia was decisive for the younger generation, as Wilhelm's sisters soon realized. Karl Stefan admitted Polish suitors to the family homestead, and married his daughters Renata and Mechtildis to Polish nobles with lofty titles and declining fortunes. The young women, Habsburg imperial princesses, had to renounce their claim and that of their heirs to the imperial throne of Austria. Although their grooms bore princely titles, the Austrian imperial court saw these unions as unequal, "morganatic" marriages incapable of reproducing the imperial blood. Yet by marrying into the Polish aristocracy the girls helped build their father's claim to a future Polish throne. Such political matchmaking was in the best traditions of the Habsburgs, and of the dynastic politics of the old Europe generally.

As for Wilhelm, the family's youngest son found himself with opinionated brothers-in-law with fancy names, Prince Alexander Olgierd Czartoryski and Prince Hieronymus Radziwiłł. As his older brothers became Polish by choice and his sisters became Polish princesses by marriage, the youngest archduke brooded over a dynastic adventure of his own: one that would set him apart from the rest of his family, and perhaps set him above those brothers-in-law.

When Wilhelm discovered and fell in love with Ukraine, he was rebelling against his Polish destiny, but also following the familial logic. He was taking his father’s dream further north, further east, to a still more neglected people.

(To be continued)

Interesting. I once met the Archduke of Habsbug, the one descended from Franz-Josef, the Emperor (his great-grandson, if I recall). Still rich. His son, or maybe grandson now, is the archduke (it was 32 years ago and he was old then). The family is still around and still rich; they're "investors" - they live around the world, everywhere but Austria, which they cannot return to. That was why we met him, in hopes he would invest in a movie. You definitely got the "imperial vibe" off him. As my associate pointed out, he could trace his family to Charlemagne, and they'd been on top most of that time. A charming guy but you definitely got the vibe you wouldn't want to cross him. That was around the time Robert Maxwell (father of the recently-convicted Ghislaine) "fell" off his boat while owing a considerable sum to someone - it was rumored that someone was the Archduke. It's pretty amazing when someone you think of as being in a history book somewhere shakes your hand and offers you a glass of pretty fine wine.

I'm looking forward to the rest of this post.

So important to understand the history. I have returned to Bloodlands for review.